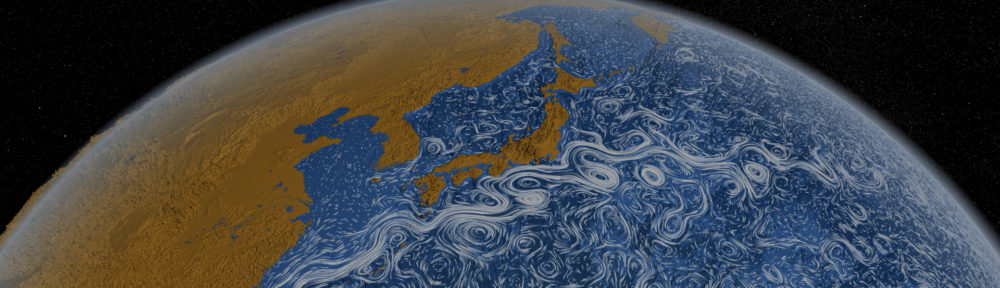

A frequent reader of this blog just pointed me to the “Breathing Earth” website, from which I took the snapshot pasted above. The site takes data about countries’ birth and death rates as well as carbon dioxide emissions and incorporates them into a single, interactive map of the world. Births and deaths show up as flashes on the world map, while the color of a country represents its carbon dioxide emissions.

What the snapshot above doesn’t show is the interactive bit of the site, which allows you to mouse over a country to learn about its particular birth and death rate as well as its carbon dioxide emissions. Plus, it features a running tally in the lower left-hand corner that shows how many people have been born, how many died, and how much carbon dioxide has been emitted since you personally opened the web page.

Overall, this strikes me as a spiffy visualization, and my initial inclination is to see more data represented—perhaps not all at the same time, since I would hate to see the pleasant design marred by overcrowding, but maybe as options. In other words, it seems like a good template. One of the challenges of presenting only a few data elements is that it suggests a causal connection between them, whereas having a more generous set of options would allow the user to explore more on her own. In terms of the content actually presented, I’m a little confused by what the color of the country really means, since the caption reads variously “country has emitted over/less than 1000 tonnes of CO2” and “is currently emitting more than 1000 tonnes of CO2.” The last statement is meaningless, since “currently” would require some rate of emission, not simply a quantity. So it seems that it could use a little more detail in the captioning.

(Then, on an utterly nitpicky note, the regular gridlines of the above image suggest a Mercator projection, but the layout of the geography looks more like the traditional Robinson projection. That annoys me, but I’m easily annoyed that way. For more on map projections, BTW, you can take a look at the “Geographer’s Craft” page or the more detailed but less complete page at USGS. For the truly anal-retentive, check out Hans Havlicek’s page for more information than most of us ever need on the topic.)

I actually took a very different approach to visualizing socio-economic data in an “art” piece I created as an interactive and for fulldome video. I dropped the map and put elements into a very abstract space, hoping to see patterns that could work on both an aesthetic and an intellectual level. Dunno if I succeeded, but I entitled it “Numerology 0.1,” if that gives any sense of how I feel about it.