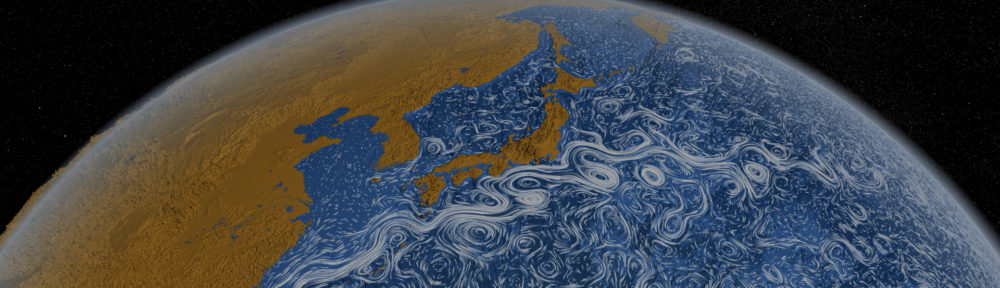

Today’s Leonard Lopate “Please Explain” focused on scientific visualization. (The image above is just a sample from an accompanying slideshow, heavily biased as it is toward medical visualizations. I happen to like it more than some of the others, but more on it later.) Lopate had two guests: Graham Johnson, a certified medical illustrator, and Felice Frankel, to whom I’ve referred previously and who started the Image and Meaning conference that’s come up previously as well.

My favorite exchange…

Lopate: “The image stay with us the rest of our life until somebody tells us that’s no longer true.”

Frankel: “And you know what? Even if they tell you it’s no longer true, that doesn’t matter…’

Exactly! Images are extremely powerful, and they become stand-ins for concepts. When an image truly settles into our brain and we know what information we can and cannot extract from it, it acts as a useful stand-in for concepts and ideas. Misinterpreted, however, or trusted too much, an image can become very misleading. Of course, reality can be misleading, too, which is why medical illustrators have kept their jobs even in the age of photography. As Johnson explained, “Our job is to pull out pertinent information and subdue the ancillary information so that we can tell a story—a particular story.” Well put.

So if you get a chance, download the MP3 and take a listen.

The above image has a great caption, BTW, in terms of presenting it in context… “Membrane Structure and Function: Used as a section overview, this figure summarizes the content of five chapters that describe the anatomy and physiology of lipid bilayers and their resident proteins. Here, the ‘water fearing’ chains of a lipid bilayer separate the cytoplasm of a cell (beige background-bottom) from the outside world (light blue background-top).”

With that explanation, I feel confident in liking the illustration even more. I even want to read the chapters!

Just as an aside, Lopate also made reference to the newly-opened Anne and Bernard Spitzer Hall of Human Origins at the American Museum of Natural History. He mentioned the design of the dioramas in the hall, the attention to detail and attempt to achieve realism. Nice to hear, since my coworker Carter and I tend to see our work on the Museum’s space shows as continuing that fine tradition. It really is a form of science visualization. (And if you’re interested in learning more about the painstaking efforts to create realistic nature dioramas, take a look at Stephen Quinn’s Windows on Nature, which came out less than a year ago. Brilliant stuff.)

Hmmm. I’ve been accused of being too upbeat this week, for which I apologize. I’ll try to find something to gripe about in the next day or so. Until then…