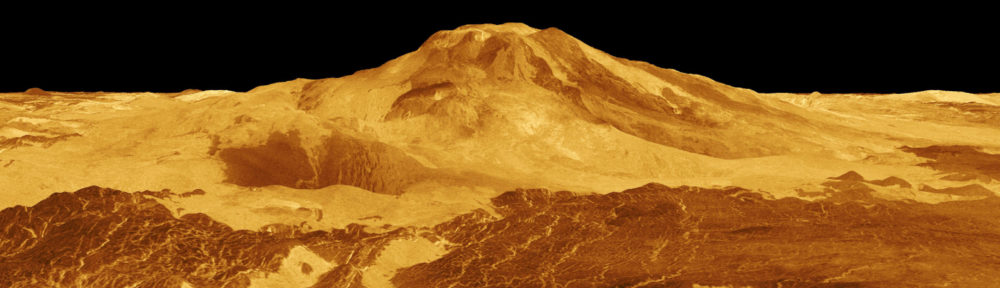

New results from the Cassini spacecraft reveal the chain of events (so to speak) that leads to the formation of complex aerosols in its atmosphere. Aside from the spiffy science, the NASA announcement includes the very nice diagram pictured above.

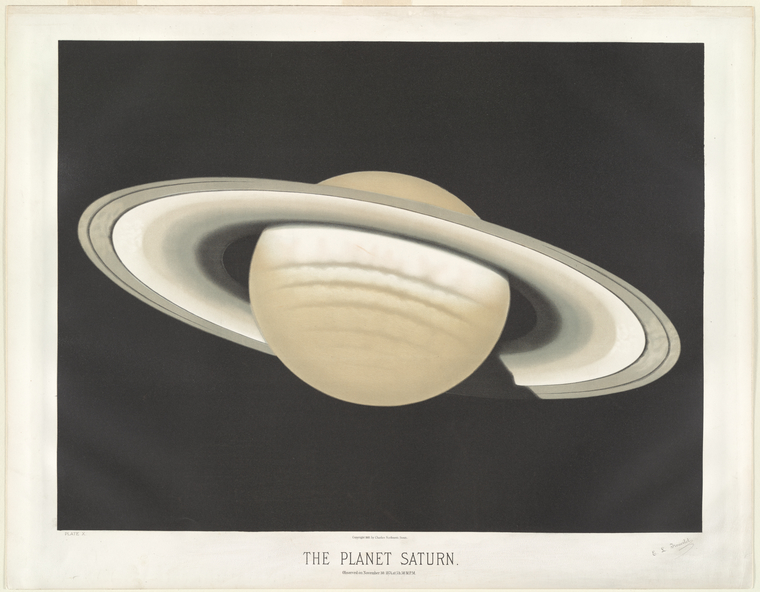

What I like about the graphic is that it tells the story very plainly and simply, yet with considerable detail and substantial visual interest: nice little PAHs and aerosols, decent image of Titan’s surface, Saturn in the background (tilted too much with respect to the ring plane, but that’s nothing new), and so on. It even includes altitude info on the right-hand side clearly indicating where specific processes take place. All in all, a lot of info packed into a single image.

And anther detail. I’m already on record as not being a fan of lens flares in the fulldome environment, and in general, I seem them as kind of cheesy. But this might be the first time I’ve seen a lens flare used as a didactic element, suggesting the flow of photons from the Sun. Nice touch!

The only thing that gives me pause is the depiction of “energetic particles” as little arrows pointing away from Saturn. The particles are trapped in Saturn’s magnetic field, so they aren’t really shooting out of the planet in straight lines, which makes that depiction a little deceptive. But then, the only real solution would be to depict Saturn’s magnetic field with particles streaming from it, and that might be a little cumbersome. So I suppose I can forgive the diagrammatic shorthand.

Another more mundane quibble. The NASA webpage for the diagram include links to smaller versions at 1600×1200, 1028×768, and 800×600, but those are all windowboxed versions of the (obviously portrait, not landscape) diagram. Thus, the only version of above image that you can download at its original aspect ratio is the full-resolution version: a whopping 2000×2776 pixels! Not the greatest for, say, linking to blog entries.

Anyway, nice work, Cassinifolk! I like the diagram. And the story it tells…